A female body is a fetish.

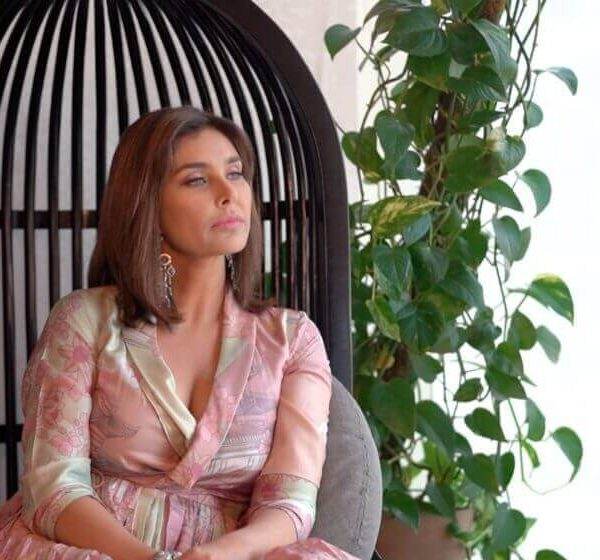

The shape of the face- oval, square, round; the cheekbones- prominent, or hidden under folds of flesh; the curve of her upper lip, the size of her ears, the contours of her body- breast to hip, give a woman her identity in this solid, sedimented world of commodification.

A famous feminist, Catherine A. MacKinnon, in one of her essays, draws a parallel between a woman and a worker. A woman is to sexuality, what a worker is to labour. In the performance of labour or of sex, the claim to profits in one case and pleasure in another lies out of the hands of these oppressed sections.

Patriarchy posits women as the passive receivers of sexuality.

The woman is the chalice which will hold the bloodline. Man, the masculine energy, will impregnate the woman and she will nurture and nourish. She will be the provider, of sex and other unrecognised services, in her domestic confinement. Women, therefore, are the objects of a discourse of which men are the subjects. The male body is addressed and taught how to view the female and derive the most out of her. This unpaid worker needs to have a healthy body and a chained mind.

The institution of marriage and the introspection of the female body at the time of fixing the deal in a marriage is a fitting example of what the meaning and objective of “looking at” a women is.

The commodification of women, their treatment as serviceable commodities has found ample expression in Indian cinema and literature. The stock scene where the conventional Indian family on the male suitor’s side visits the family of the bride under consideration presents a codified, institutional analogue of the “looking at” women that we find on the roadside, in a gym, or at other public places where women are eve-teased (which is, generally, everywhere).

Even in discourses that address women, are we not making women the objects of an experiment where they tend to be viewed through the eyes of a male dominated world, or generally, a world where women’s discourses are co-opted and get embedded in larger profit-making capitalist schemes.

Is not the image of a free, economically independent woman circulated along with a series of bourgeois perfumes, beauty products, anti-ageing creams, and isn’t the image strongly created such that the feminist discourse only gets exploited by a capitalist strategising force? Does not the female body again collapse into a structure where it is the object that benefits, if not one structure, then the other that is connate with it? Is not the image of a working woman always attached with the image of a neglecting mother, or an indifferent wife, in popular culture?

All this might also remind you of the new ideal woman- who caters to capitalism and patriarchy simultaneously. These women will wake up , make breakfast for the whole family, then eat themselves before leaving for a job, use all the products that they are required to in order to keep up appearances at the workplace, then come back home and be all over their place managing everything with superhuman strength. This is the image. This is what patriarchy alludes to women, and this is what it searches for when it looks at them.

Men are the free-floating human entities that remain undefined and unmarked; females are set in a cast from the moment they are born.

Though, contemporary feminist and queer feminist discourses debate thoroughly, and obscurely for an ordinary consumer of literature and political theory, the subject-object dichotomy for men and women would be the easiest way to go about it. Judith Butler might have complicated as well as unintertwined the politics of sexuality for us, but the difference that she elaborates exists between Luce Irigaray, Simone de Beauvoir and Wittig in the realm of language and its application, is not something we would want to attempt here. Let us not enter the sphere of obscure political theory, and observe the existing contrast between how male and female bodies are witnessed around us.

Men are “seen”, women “ looked at”. Women being “looked at” has very serious connotations. This phrase carries the burden that a female body bears throughout her life- the burden of going on living a controlled and predetermined trajectory of licensed behaviour. Every “look” at the female body is somehow an investigation to inform patriarchy of her conformity and treat her as a legitimate female subject whom the society does not deny the identity that it already wants to associate with women. The male gazes at the female to give her “recognition” as the accepted female- the character of homeliness, docility, submission that is attached to the ideal woman, or to reject her as the non-conformative threat to patriarchy- the woman who appears to be not the passive receiver but the agent and author of her sexuality and existence, the one termed a “slut” and many such names.

However, in both cases, women’s bodies are viewed as objects that would provide pleasure in the form of sexual service.

The anatomical study of a woman’s body parts while looking at her is the most filthy practice bred by phallogocentrism. The sexualisation of breasts, of a woman’s buttocks, thighs and every other part in seclusion is the essence of this gaze that scrutinises women and turns them into sexual objects. This comes with a detachment of the female body from the thinking, feeling being that she is.

A woman, striving for recognition in a male-dominated world, accepts the unspoken rules of patriarchy and “presents” herself to the gaze that examines her.

While men are the Sartrian subjects and authors of their life, the female lives are to “be” as they are directed. The activities of men , and their bodies as presences, are witnessed; those of women are seen and investigated to draw inferences